SII Focus 7th July 2017

WADA do about WADA’s bad science?

An analysis of the key cases in which a lack of scientific evidence and protocol have gravely undermined WADA’s role in anti-doping.

2016 was a difficult year for WADA, the World Anti-Doping Agency. The failure to act sooner on the information of whistleblowers made regular headlines. An inability to enforce consistent standards across National Anti-Doping Organisations (NADOs) became an ongoing concern. WADA’s transparency and governance were brought into question. The biggest sporting event in the world became notorious not for on-field achievements, but for a sweeping ban on one country’s athletes.

These wider public problems resulted in WADA becoming, by its own admission, ‘largely occupied by investigations and related activities’. With attention turned elsewhere, scrutiny of the very processes upon which WADA bases, and implements, its World Anti-Doping Code have been found wanting. Flagged as a concern over a decade ago, but lacking the public appeal of a systemic doping scandal, WADA has failed, at critical times, to properly interpret basic scientific data, conduct appropriate studies, and provide proper instructions and notifications to athletes.

WADA’s disregard for scientific evidence and protocol have been devastating to the very population it is trying to protect – clean athletes. Those that violated the Code found themselves victims of an arbitrary and opaque process. Below The Sports Integrity Initiative explores these underreported shortcomings, with exclusive access to the scientists and lawyers who uncovered WADA’s errors.

Meldonium

In January 2016 match-fixing appeared to be the biggest threat facing tennis, as evidence of irregular betting surfaced at the Australian Open. By early March however the sporting world was stunned as Maria Sharapova, tennis’ highest profile athlete, announced that she had been provisionally suspended for having taken a hitherto little-known drug – meldonium.

Google searches for the term sky rocketed. The ensuing coverage simply accepted WADA’s carefully worded explanation that it had been added to the Prohibited List ‘because of evidence of its use by athletes with the intention of enhancing performance’. Very few asked how it might produce such an effect, just that it did.

Between 1 January 2016, the date meldonium became prohibited, and 3 May 2016, there were nearly 300 adverse analytical findings for meldonium. The violations fitted in neatly with the narrative of Russian systemic doping, with the findings emanating almost exclusively from Eastern Europe. It all made sense. Unfortunately for WADA, there were serious shortcomings.

Meldonium excretion

Firstly, it quickly appeared that many athletes who had stopped taking meldonium before the cut-off date of 1 January 2016 were testing positive months afterwards. Confusion ensued over how long meldonium remains in the body, and how slowly it is excreted. It wasn’t until April 2016 that WADA acknowledged the potential for meldonium to remain in the body for far longer than it had previously assumed (or even guessed). Come June, the organisation admitted that it had not yet even conducted, nor seen, studies that would allow it to make an assessment in that regard.

Performance-enhancing?

Secondly, there remain legitimate questions as to why meldonium was added to the Prohibited List in the first place. According to Mike Morgan, who acted for a number of athletes involved in meldonium cases, WADA banned meldonium based in part on ‘scant and scientifically unsound literature identifying its potential to enhance performance’.

Morgan, who also represented Maria Sharapova in her successful appeal against her suspension by the International Tennis Federation (ITF), revealed that the primary study that WADA appeared to rely on tested performance in just one sport. This sole report was based on seven judokas taking meldonium against a control group that was on average seven years younger and 23 kilograms lighter[1].

Two other scientific papers that WADA appeared to rely on recycled the data of the aforementioned study[2],[3]. Marketing claims made by certain manufacturers and retailers of meldonium were further used to support WADA’s assertions, despite the obvious sales agenda. Respected scientific experts have continued to express their concern that, in reality, there is ‘no scientific evidence of the performance enhancing properties of meldonium’ [4].

Perhaps the most worrying element of the meldonium affair is that this isn’t the first time that concerns have been raised over WADA’s reliance (or lack of) on scientific evidence. For example, in respect of methylhexaneamine – a substance for which Yohan Blake and other Jamaican sprinters tested positive in 2009 – Peter L. Ruddock, PhD, a medicinal chemist and expert witness in that case, commented:

The situation is made more complicated by the absence of any scientific data which support the view of any performance-enhancing properties of methylhexaneamine. Indeed, the only study that I am aware of that investigated this (in searching more than 100 years of scientific literature) is a 2011 paper by Richard Bloomer et. al. in the Journal of Caffeine Research. The study showed that methylhexaneamine had no effect at all on athletic performance. Why is methylhexaneamine on the list then? Only WADA can say. […] WADA must present hard scientific facts on the banned substances in every single case to support sanctions. The scientific studies to date do not show any evidence that methylhexaneamine enhances athletic performance, yet the substance carries a severe penalty.

Methylhexaneamine remains on the latest version of the Prohibited List, whereas caffeine, a stimulant that – according to a number of studies conducted across decades (see here and here for examples) – can indeed enhance performance, no longer does, and probably never will.

Incommunicado

In addition to the above, WADA failed to issue any specific notices to athletes alerting them to the change in status of meldonium. Nor did it require its signatories to do so, despite the ease and cost-effectiveness of such publicity. Meldonium may not be approved for use by the FDA in the USA, but it is commonly used in Eastern Europe – becoming registered in 17 counties in the period 1988 to 2007. WADA was well aware that an enormous number of athletes were using meldonium – this in fact appeared to have been one of the other key reasons WADA decided to add meldonium to the Prohibited List. Yet it took no specific steps to ensure that those athletes would be notified of the change in status.

Higenamine

Running alongside the meldonium affair, WADA quickly found itself embroiled in another similar case. It is one that is well documented on this site, and although it highlights the plight of just one clean athlete, the repercussions have implications for many more.

In April 2016 the Liverpool footballer Mamadou Sakho tested positive for higenamine. On the face of it, a run-of-the-mill anti-doping violation. Only it wasn’t, because higenamine didn’t even feature on the 2016 Prohibited List.

Sakho, who served a provisional suspension that kept him out of the UEFA European Championships and the Europa Cup Final, successfully argued that there is no evidence confirming that higenamine is, in fact, a beta-2 agonist in humans. The relevance of this was that Sakho’s case had only arisen because WADA had decided to treat higenamine as a beta-2 agonist – a specific category of banned substances. The case started and finished on this point alone.

Sakho’s defence was based on the evidence of scientific experts, which included a Nobel Prize winner. By contrast WADA was arguing from a position in which not all of its accredited-laboratories were testing for the substance, in which it had never issued a statement or warning about the substance to either athletes or laboratories and in which it relied on a handful of scientific papers which either contradicted each other or bolstered Sakho’s defence.

With this overwhelming evidence against WADA, it is perhaps not surprising that it chose not to make any representations at Sakho’s hearing, nor send anyone from the organisation. Sakho was exonerated on all counts.

Again, this isn’t the first time WADA has been found wanting in relation to its classification criteria. In 2004 the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS) set aside the International Olympic Committee’s (IOC) disqualification of Colombian cyclist Calle Williams following that summer’s Olympic Games, returning to her the bronze medal which had been stripped from her. Williams had tested positive for isometheptene, which WADA claimed was banned on the basis that it was a stimulant ‘similar’ to those that were on the Prohibited List, despite not specifying which stimulants it was supposedly similar to nor how it was similar. Same, same but different.

In Rushall and Jones’ 2006 paper, they complain that ‘WADA has created its own committees to develop a unique categorization [sic] of banned substances. One has to question why committee members have not adhered to professional standards and demanded the use of accepted labels for classes of substances.’ Little, it would appear, has changed in the last decade.

Higenamine, incidentally, is now explicitly named in the 2017 Prohibited List, identified as a Beta-2 Agonist. This is despite no new scientific evidence to support this classification.

19-Norandrostenedione

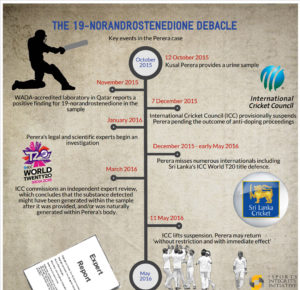

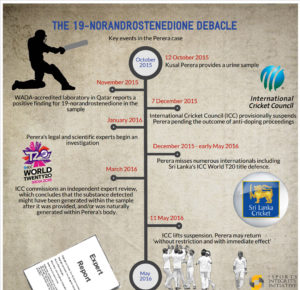

In late 2015, the Sri Lankan international cricketer Kusal Perera was suspended by the International Cricket Council (ICC) after testing positive for the anabolic steroid 19-Norandrostenedione. Seven months after providing the initial urine samples however, all charges were dropped.

Listed on WADA’s 2015 Prohibited List as an exogenous (not naturally produced) substance, it was subsequently found after scrutiny of the laboratory results by Perera’s lawyers – Morgan Sports Law – that the substance detected was either (a) generated within Perera’s sample after it was provided, and/or (b) naturally generated within Perera’s body (i.e. endogenously). Not only was there an issue with the exogenous classification (the substance is now listed as endogenous), but it raises serious questions over WADA’s testing instructions and the procedures of its accredited laboratories.

The ICC in its statement exonerating Perera noted how ‘troubled’ it was by the fact that the WADA-accredited Qatar laboratory had issued an Adverse Analytical Finding which ‘then had to be withdrawn and replaced with an Atypical Finding.’ The head of the laboratory, Costas Georgakopoulos, in return, placed the blame firmly on WADA’s instructions, reportedlysaying that the error was ‘nothing to do with the laboratory, it’s to do with the interpretation, the procedure.’

Despite not publicly accepting any responsibility, on the same day that the ICC dropped its charges, WADA approved revised instructions to laboratories for their testing for and reporting on the steroid in question. The instructions provide no reference to Perera’s case. WADA also reclassified the substance as endogenous (i.e. naturally produced) in its next version of the Prohibited List.

Conclusion

In 2006 Rushall and Jones wrote in length of their concerns over ‘the number of innocent athletes who are paying the price for a flawed anti-doping system.’ A decade on and serious questions remain.

In its 2017 new year message to stakeholders, WADA speaks of its ‘energy and optimism’. Its press release emphasised one area in particular – its intent on bolstering ‘WADA as the only international regulatory body overseeing clean sport’.

While we contemplate the next decade in the fight against doping, it is perhaps fitting to reflect on the conclusions of a couple of scientists (Rushall and Jones) who themselves hoped for a better decade ahead:

‘When a social order remains unchecked, social disorder usually results – social entropy being the outcome from inwardly focused organizations [sic]. Through the failure of both WADA and the scientific community to perform adequate scientific work in a field that should be based in science, a gradual decrease in social value of WADA and an increase in its social threat have resulted.’

Should we really be accepting WADA as the de facto modern, and only, standard? If it is, many improvements need to be made, and those of us as journalists, scientists and lawyers in sport, have a duty to hold them to those standards.

[1] Kakhabrishvili Z. et al. Mildronate effect on physical working capacity among highly qualified judokas. Ann. Biomed. Res. Edu. 2002, 2, 551.

[2] Dzintare M, Kalvins I. Mildronate increases aerobic capabilities of athletes through carnitine-lowering effect. 5th Baltic Sport Science Conference: Current issues and new ideas in sports science; 2012 Apr 18-19; Kaunas, Lithuania.

[3] Görgens C et al. Mildronate (Meldonium) in professional sports – monitoring doping control urine samples using hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography – high resolution/high accuracy mass spectrometry. Drug Test Anal. 2015 Nov-Dec;7(11-12):973-9. doi: 10.1002/dta.1788.

[4] Schobersberger W, et al. Story behind meldonium-from pharmacology to performance enhancement: a narrative review. Br J Sports Med. 2017 Jan;51(1):22-25. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096357. Epub 2016 Jul 27.

Комментариев нет:

Отправить комментарий