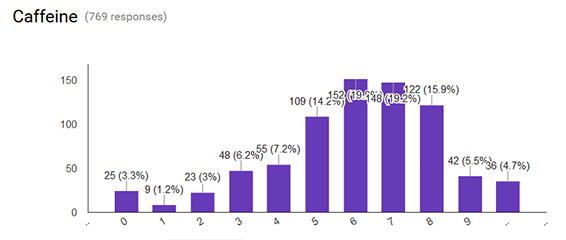

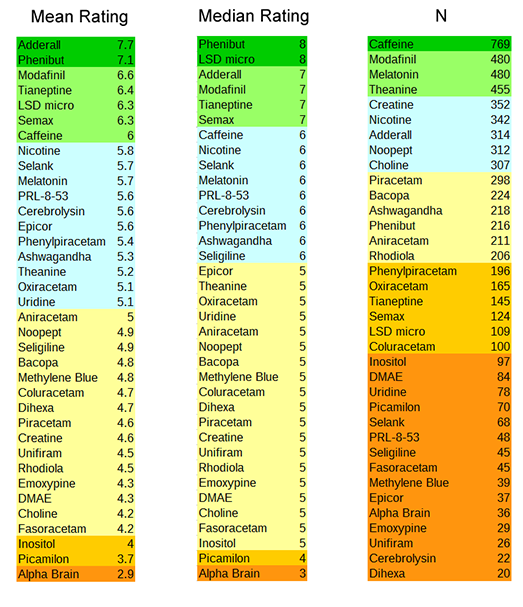

Результаты опроса на тему какие вещества работают, а какие плацебо в плане когнитивного улучшения. N — количество голосов, люди голосовали за вещество которое попробовали; median — медиана, mean — среднее значение. В списке не все ноотропы.

источник

http://slatestarcodex.com/2016/03/01/2016-nootropics-survey-results/

Median rating, mean rating, and sample size for each nootropic. You can find more information on the individual substances here

Percent of responders who rated each nootropic at least five (the middle rating) or ten (the highest rating)

источник

http://slatestarcodex.com/2016/03/01/2016-nootropics-survey-results/

2016 NOOTROPICS SURVEY RESULTS

[Disclaimer: Nothing here should be taken to endorse using illegal or dangerous substances. This was a quick informal survey and you should not make any important health decisions based on it. Talk to your doctor before trying anything.]

Nootropics are traditionally defined as substances that improve mental function. In practice they usually refer to psychoactive chemicals that are neither recreational drugs like cocaine and heroin, nor officially-endorsed psychiatric drugs like Prozac or Risperdal. Most are natural supplements, foreign medications available in US without prescription, or experimental compounds. They promise various benefits including clearer thinking, better concentration, improved mood, et cetera. You can read more about them here.

Although a few have been tested formally in small trials, many are known to work only based on anecdote and word of mouth. There are some online communities like r/nootropics where people get together, discuss them, and compare results. I’ve hung out there for a while, and two years ago, in order to satisfy my own curiosity about which of these were most worth looking into, I got 150 people to answer a short questionnaire about their experiences with different drugs.

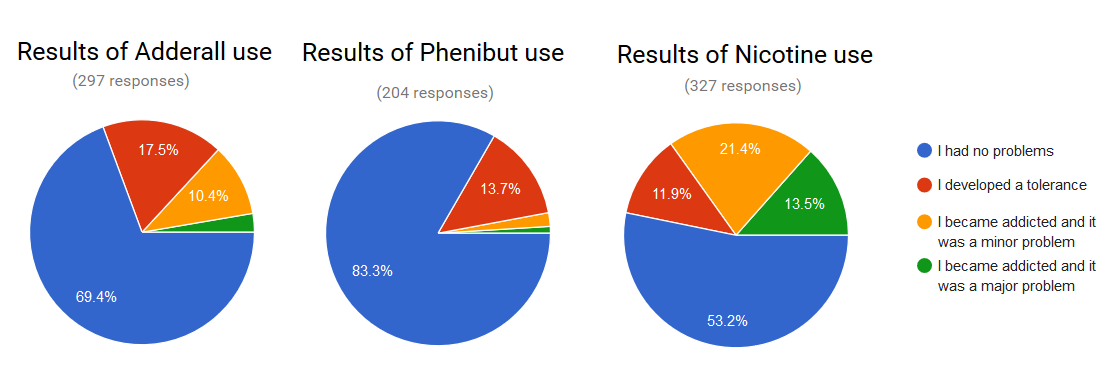

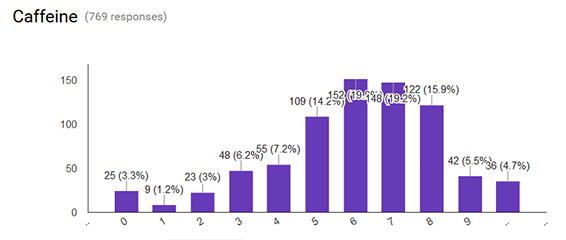

Since then the field has changed and I wanted to get updated data. This year 850 (!) people agreed to fill out my questionnaire and rate various nootropics on a scale of 0 – 10 – thanks again to everyone who completed the survey.

Before the results themselves, a few comments.

Last time around I complained about noisy results. This year the sample size was five times larger and the results were less noisy. Here’s an example: the ratings for caffeine form a beautiful bell curve:

Even better, even though this survey was 80% new people, when it asked the same questions as last year’s the results were quite similar – they correlated at r = 0.76, about what you’d get from making students take the same test twice. Whatever’s producing these effects is pretty stable.

A possible objection – since this survey didn’t have placebo control, might all the results be placebo? Yes. But one check on this is that the different nootropics controlled against one another. If we believe that picamilon (rated 3.7) is a placebo, this suggests that PRL-8-53 (rated 5.6) does 19 percentage points points better than placebo.

But might this be confounded by lack of blinding? Yes. That is, if companies have really hyped PRL-8-53, and it comes in special packaging, and it just generally looks cooler than picamilon, maybe that would give it a stronger placebo effect.

Against this hypothesis I can only plead big differences between superficially similar drugs. For example, rhodiola and ashwagandha are both about equally popular. They’re both usually sold by the same companies in the same packaging. They’re both classified as “adaptogens” by the people who classify these sorts of things. But ashwagandha outperforms rhodiola by 0.9 points, which in a paired-samples t-test is significant at the p = 0.03 level. While you can always find some kind of difference in advertising or word-of-mouth that could conceivably have caused a placebo effect, there are at least some reasons to think something’s going on here.

Without further ado, here’s what I found:

Some very predictable winners: Adderall is a prescription drug and probably doesn’t even qualify as a nootropic; I included it as a reference point, and it unsurprisingly did very well. LSD microdosing is the practice of taking LSD at one-tenth or less of the normal hallucinogenic dose; users say that it improves creativity and happiness without any of the typical craziness. Phenibut is a Russian anxiolytic drug of undenied effectiveness which is sort of notorious for building tolerance and addiction if used incorrectly. And modafinil is a prescription medication for sleep issues which makes users more awake and energetic. All of these are undeniably effective – but all are either addictive, illegal without prescription, or both.

I’m more interested by a second tier of winners, including tianeptine, Semax, and ashwagandha. Tianeptine is a French antidepressant available (legally? kind of a gray area) without prescription in the US; users say it both provides a quick fix for depression and makes them happier and more energetic in general. Semax is a Russian peptide supposed to improve mental clarity and general well-being. Ashwagandha might seem weird to include here since it’s all the way down at #15, but a lot of the ones above it had low sample size or were things like caffeine that everyone already knows about, and its high position surprised me. It’s an old Indian herb that’s supposed to treat anxiety.

The biggest loser here is Alpha Brain, a proprietary supplement sold by a flashy-looking company for $35 a bottle. Many people including myself have previously been skeptical that they can be doing much given how many random things they throw into one little pill. But it looks like AlphaBrain underperformed even the nootropics that I think of as likely placebo – things like choline and DMAE. It’s possible that survey respondents penalized the company for commercializing what is otherwise a pretty un-branded space, ranking it lower than they otherwise might have to avoid endorsing that kind of thing.

(I was surprised to see picamilon, a Russian modification of the important neurotransmitter GABA, doing so badly. I thought it was pretty well-respected in the community. As far as I can tell, this one is just genuinely bad.)

Finally, a note on addiction.

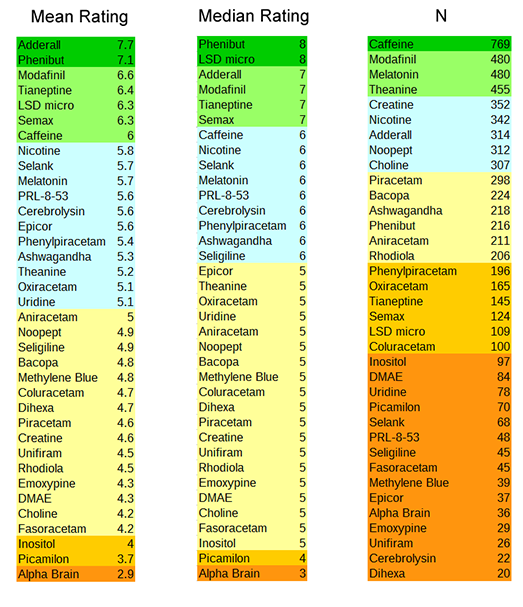

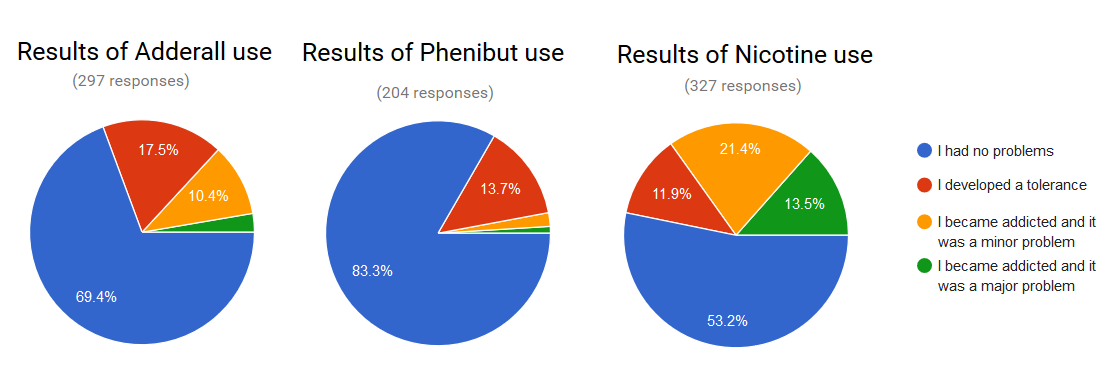

Adderall, phenibut, and nicotine have all raised concern about possible addictive potential. I wanted to learn a little bit about people’s experiences here, so I asked a few questions about how often people were taking things at what dose and whether they got addicted or not.

In retrospect, these were poorly phrased and didn’t get me the data I wanted. When people said they were taking Adderall every day and got addicted, I didn’t know whether they meant they became addicted because they were using it every day, or that they were using it every day because they were addicted. People gave some really weird answers here and I’m not sure how seriously I can take them. Moving on anyway:

A bit under 15% of users got addicted to Adderall. The conventional wisdom says “recreational users” are more likely to get addicted than people who take it for a psychiatric condition with a doctor’s prescription. There was no sign of this; people who took it legally and people who took it for ADHD were actually much more likely to get addicted than people who described themselves as illegal or recreational users. In retrospect this isn’t surprising; typical psychiatric use is every day; typical recreational use is once in a while.

Only 3% of users got addicted to phenibut. This came as a big surprise to me given the caution most people show about this substance. Both of the two people who reported major addictions were using it daily at doses > 2g. The four people who reported minor addictions were less consistent, and some people gave confusing answers like that they had never used it more than once a month but still considered themselves “addicted”. People were more likely to report tolerance with more frequent use; of those who used it monthly or less, only 6% developed tolerance; of those who used it several times per month, 13%; of those who used it several times per week, 18%; of those who used it daily, 36%.

Then there was nicotine. About 35% of users reported becoming addicted, but this was heavily dependent upon variety of nicotine. Among users who smoked normal tobacco cigarettes, 65% reported addiction. Among those who smoked e-cigarettes, only 25% reported addiction (and again, since there’s no time data, it’s possible these people switched to e-cigarettes because they were addicted and not vice versa). Among users of nicotine gum and lozenges, only 7% reported addiction, and only 1% reported major addiction. Although cigarettes are a known gigantic health/addiction risk, the nootropic community’s use of isolated nicotine as a stimulant seems from this survey (subject to the above caveat) to be comparatively but not completely safe.

I asked people to name their favorite nootropic not on the list. The three most popular answers were ALCAR, pramiracetam, and Ritalin. ALCAR and pramiracetam were on last year’s survey and ended up around the middle. Ritalin is no doubt very effective in much the same way Adderall is very effective – and equally illegal without a prescription.

People also gave their personal stacks and their comments; you can find them in the raw data (.xlsx, .csv) or the fixed-up data (.csv, notes). If you find anything else interesting in there, please post it in the comments here and I’ll add a link to it in this post.

EDIT: Jacobian adjusts for user bias

Комментариев нет:

Отправить комментарий